My very first experience teaching formally at a university also happened to occur during the peak of the pandemic, amid a number of other historic “firsts”. As a result, there was a lot of trial and error necessary (and in a very short time frame) as many things that worked for previous classes needed adjustments. Below, I briefly chronicle my experience as a graduate student instructor, and instructor of record for SI 330: Data Manipulation in Python.

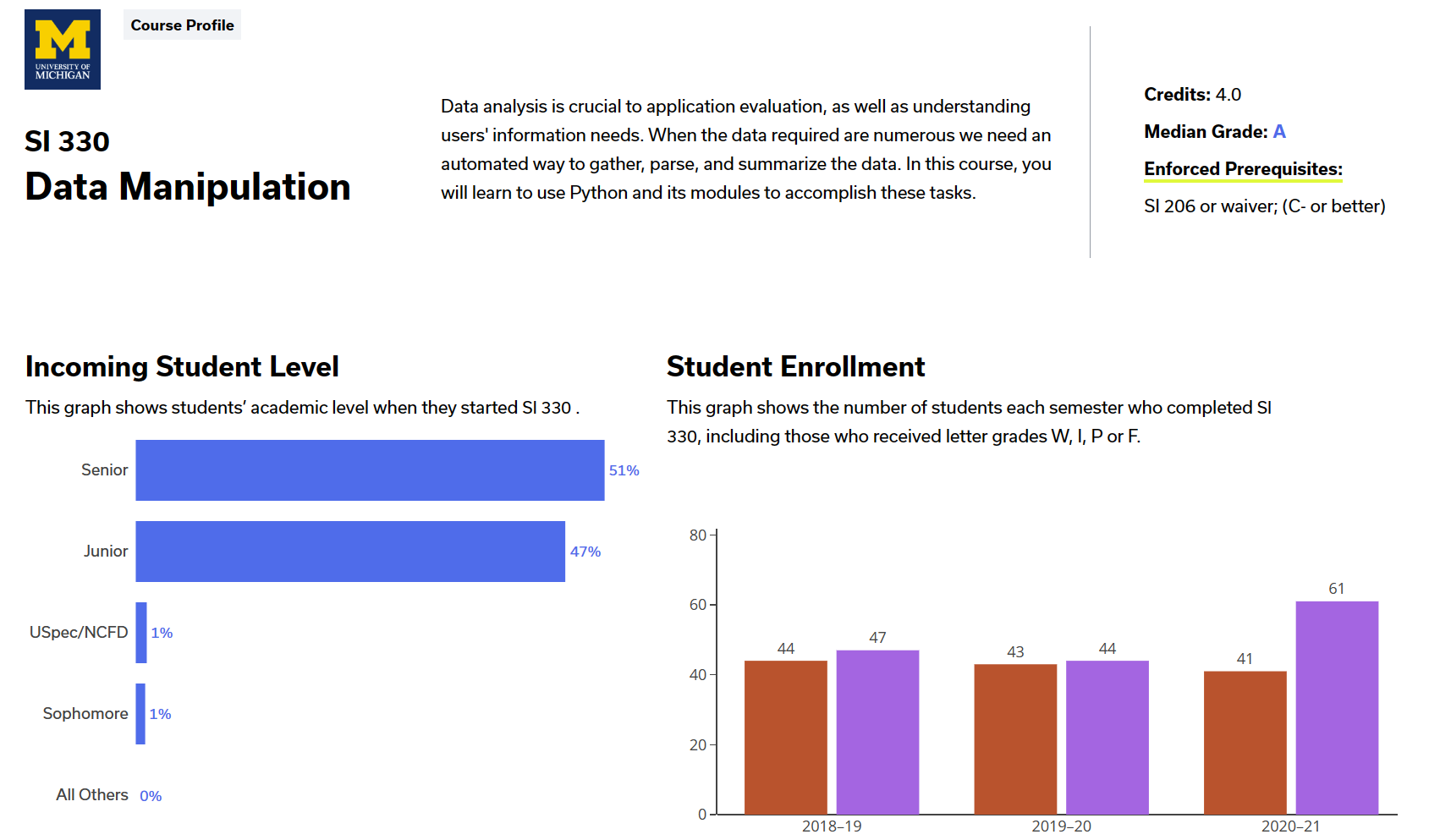

For context, undergrate students at UMSI take a slate of general education courses during their 1st and 2nd years, which includes courses from the School of Information. However, they must choose either the User Experience (UX) or Information Analyst (IA) path in the 3rd year and apply formally. SI 330 is the foundational course in the IA path, and for many, their second programming-intensive course after introductory Python.

Consequently, the content coverage is large and the workload is relatively heavy. Topics discussed include: numpy, scipy, pandas (in particular, broadcasting and vectorized operations), as well as SQL, databases, and a brief foray into machine learning and big data. With that said, the exact contents change from year to year as there will have been 6 different instructors (including myself) in 5 years (2018-2023).

GSI Experience: Creating Group Work…Online

Challenges and Opportunities

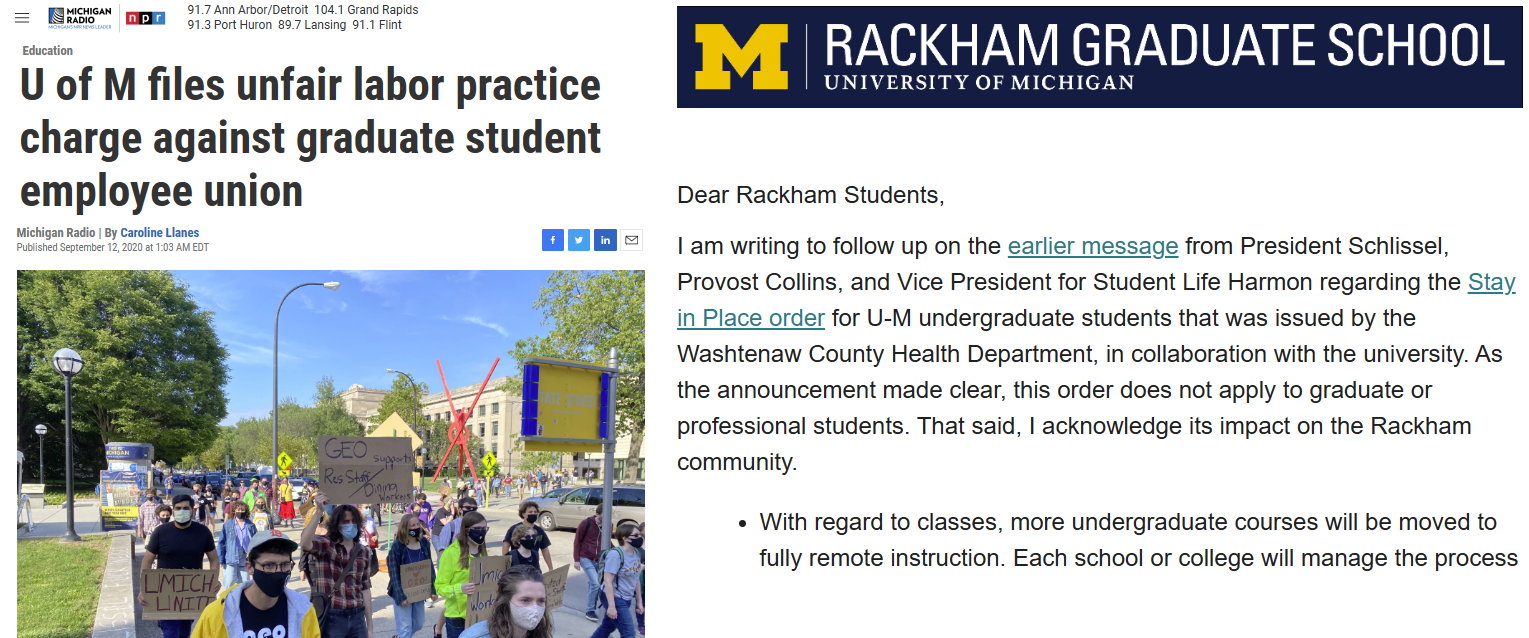

- Strike: This was going to be the first semester with an in-person component, after the previous semester was interrupted by COVID. There was significant controversy and concern over health and safety of students and staff, resulting in strike action from the Graduate Employees’ Organization (GEO). Consequently, learning was disrupted during the beginning of the semester with the cancellation of discussion sections during week 1 and 2.

-

Shifting Modalities: Originally, I had organized lab sessions where students could have the option to either come into a large spaced-out lecture hall or remain online to offer maximum flexibility. This was a bit difficult to manage, and so I had an instructional assistant help monitor for questions online. With that said, due to the rise in cases, all in-person was eventually suspended halfway through the term, which led to additional reorganization.

-

Learning Loss: A pretest was given to students at the begnning of the semester. We found that a portion of the content that students were expected to know was not all covered, in part, due to the constant disruption in learning. This would continue throughout the academic year, and so more time was dedicated to review of fundamental programming skills (data types, functions, etc.).

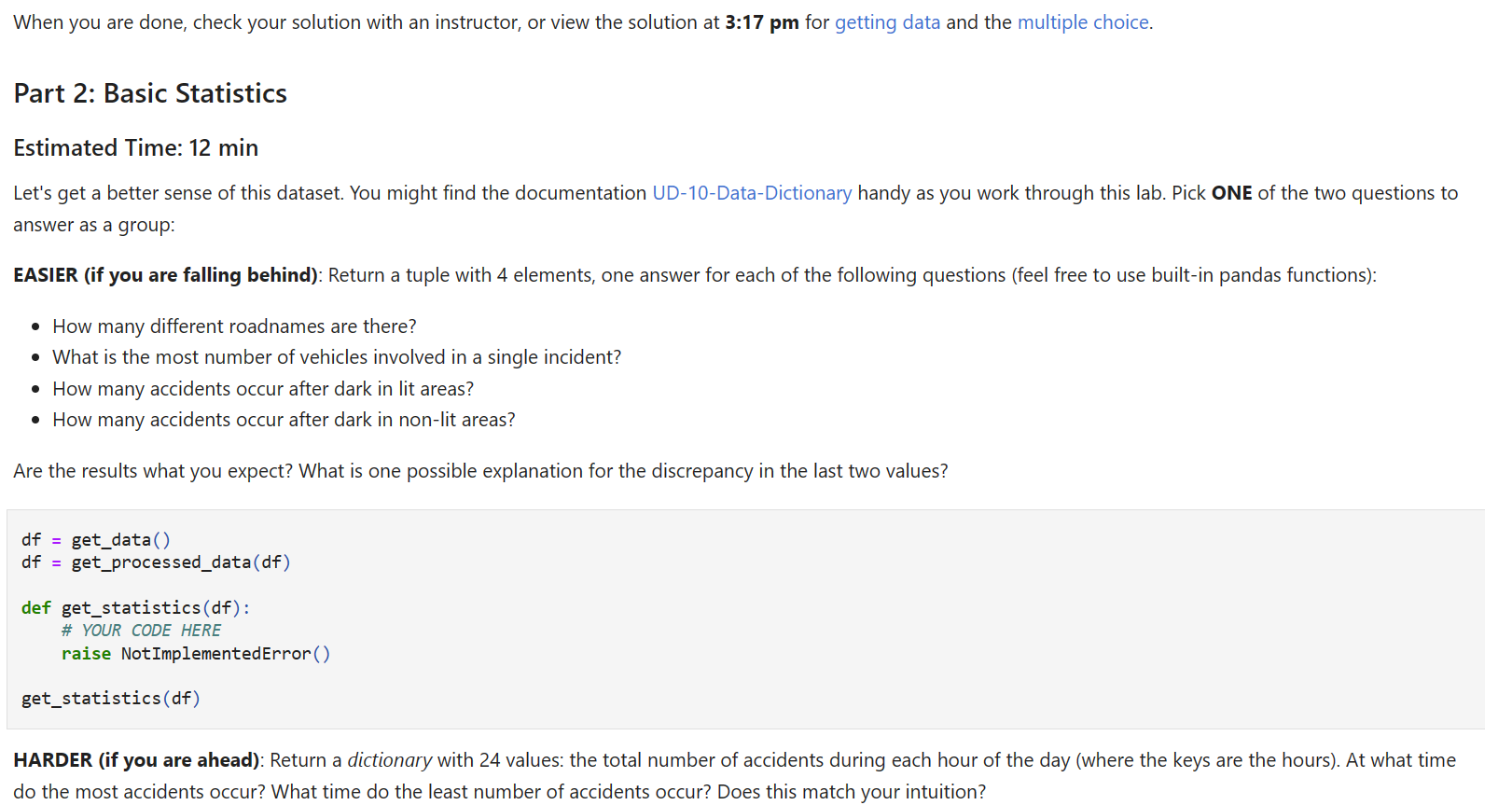

Content and Techniques

- Active Learning: In order to reinforce the concepts taught during the primary lecture, I created a set of collaborative lab activities where students work in small groups to complete a data analysis activity. I tried to pull from real datasets (which are sometimes messy) and documentation whenever possible, to answer questions that people might be actually interested in. They are also tailored to different skill levels and solution videos were provided as well after a set delay to prevent falling too far behind.

-

Social Interaction: One of difficulties with a fully online semester is that many students did not have many opportunities to interact. Consequently, I tried to incorporate different tools (given the limited course budget) to engage with each other such as Wonder or Gather Town. However, at the time, some students encountered connection difficulties that were difficult to troubleshoot online. As a result, we stuck with Zoom, but I tried to prearrange breakout rooms where people could choose in advance, and some told me after the fact that they were able to make friendships and meet up (outside of class) later in the year!

-

Frequent Feedback: After every class, I would include a short reflection, which helps promote metacognitive skills and lets me adjust my pedagogy. However, since these are associated with lab assignments, I agree (with others that have also later given me this suggestion) that I should solicit anonymous feedback halfway through the course.

Instructor of Record: Challenges and Lessons Learned

Typically, in our department (as well as many other STEM domains across the university), graduate students are not permitted to be the formal instructor of record. Even as a GSI for SI 330, I was already given much more freedom in running the discussion sections, whereas these activities are often prescribed. However, due to a shortage during the 2021 Winter semester and my positive relation working with the previous instructor, the Associate Dean offered me a one-time postition. As a result, I took many pedagogical risks and pushed the design of the course to try a number of novel techniques that I might not get the opportunity to do as a new faculty member. Some of these worked well, but some could use improvement.

Challenges and Opportunities

-

Online-Only Semester: while I did have roughly a month to prepare prior to the course beginning, and some of the content (such as the labs I created in the prior semester) could be reused, much of the lectures and homework required reworking or rebuilding from scratch. Since the course has gone through many instructors and was usually conducted in-person, there was little standardization and activities that may have worked well sitting in pods required adjustments for an online environment.

-

Growing Department: the department and its programs have also been steadily growing in size over the years. I was informed that there are usually about 50 students, but this semester was actually a record with over 60 students. Part of the influx was due to the fact that study-abroad programs were suspended. With that said, some students kept studying from abroad due to a number of reasons (visa issues, etc.). Consequently, I also manged and scheduled lab sessions and office hours to accomodate a variety of time zones.

-

Mental Health: the impacts of COVID extended beyond my own teaching plans, of course. A number of students were still struggling and many became ill throughout the semester or worried about other family members getting sick. While this was supposed to be the first semester returning to the “normal” grading scale from a temporary “pass/no record” system, it was still necessary to incorporate flexbility in assignment deadlines. Additionally, my graders and GSI (who were awesome and vitally important) also had their own personal challenges during the semester. Consequently, as a teaching team (who all had our own course/research responsibilities), I also had to address their health needs to keep the course running smoothly, and so at certain points, we mutually decided to drop homework assignments to reduce the grading load or modify rubrics as needed.

Innovations and Risks

-

Streamlining Grading: I had already used a number of tools in the past term such as Jupyter’s nbgrader extension and Github classroom. However, since it was only 1 GSI (me) doing all the grading, I did not have to discuss with anyone else. In this case, where I had to manage a team, we needed someway to collaborate and keep track of tasks. As a result, I decided to incorporate CodePost into our workflow, which worked well. I also used Deepnote so that students could collborate a bit more naturally during labs (think Google Docs but for code). Of course, the downside with many tools is that students lose track of where things are. This can be partially alleviated by including everything centrally in a good LMS, but this is where some mistakes occured.

-

Gamified Learning: I wanted to try gamified learning and offer different ways to obtain points. The maxmimum point total was large (15,000) and the amount required for an A was 10,000. The hope was that even though this meant it would be hard to earn “perfect scores” on individual tasks, there would be less pressure to do so. However, this backfired in reality. Many felt pressured to do all the things, and felt it was difficult to keep track of their point totals. I thought about using an LMS developed at UM for this purpose (GradeCraft), but talked to another faculty member who warned me against using too many new tools. However, instead of taking the leap anyway or firmly sticking with Canvas, I thought I could customize Google Classroom to fit my purposes (since it didn’t require a separate login) and provided a spreadsheet to track progress; this ended up being the worst of both options as it wasn’t designed to handle such a grading scheme and students were unfamiliar with it. Much of the contention in student comments were understandably about this point. Fortunately, this is a relatively simple fix for future iterations.

-

Videos and Midterm Conferences: This class was also partially flipped. For the Thursday lecture, students would watch and following along with a prerecorded YouTube video with an embeded task to make sure people were following along. This was a fun activity and I had students tell me online that they found the videos both engaging and useful (see playlist below; first lecture was of lower quality, but the rest are improved). However, this was admittedly difficult to produce/edit/publish on time especially when my probation deadline for PhD candidacy came midway through the term.

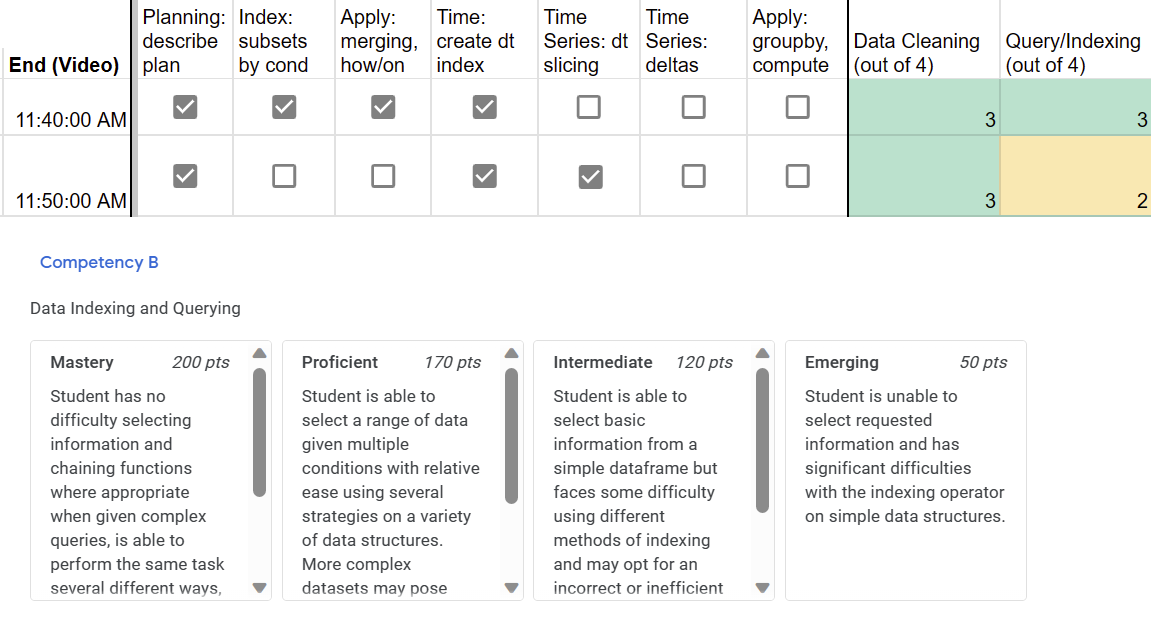

- Midterm Conferences: Cheating and academic integrity became a large issue during this pandemic period. As a result, class averages in departments such as Electrical Engineering and Computer Science saw increases in test averages (and countered by curving), while other students in prorams such as Nursing relied on more surveillance and detailed proctoring. I chose to give a live exam for 3 reasons: it is good practice for coding interviews (applicable); I am interested in understanding if students can reason through a problem with the learned concepts rather than regurgitating facts; the issue of cheating is mitigated without it having to feel like an “us versus them” situation. With that said, scheduling 60 interviews in a week was a logistical puzzle.

In short, we opened 10 minute slots from 10am-3pm (with a 1 hour break) on 2 days with me, my TAs, and GSI working in pairs. Students were given the data set and sample tasks a week in advance, a list of skills covered, and would arrive and spend 10 minutes in a Zoom waiting room where they could read the prompt and plan. Then, they would enter the main room for a 10 minute session with the TA for more limited tasks followed by a 10 minute session with me or the GSI. Finally, students were given a link with a few multiple choice and survey questions. As one student would leave the waiting room, the next student would arrive. Students were asked to work the problem out live, explain their thought process, and were graded on a 4-point rubric for each relevant skill. This meant we could allocate about (6 slots/hour)*(4 hours/day)*(2 days)*(2 pairs) = 96 slots, where each student would spend about 40 minutes total.

You can see in more detail how I incorporated everything in my syllabus.

All in all, while certainly not perfect, things were relatively solid given the circumstances, and these were good learning experiences with lots of lessons to apply in my future teaching.